our story

(as told by Megan Hill of Eater Seattle on 8/17/20)

The Story of Beloved Phnom Penh Noodle House’s Emotional Comeback

Through personal tragedy and now a pandemic, the International District treasure has been remarkably resilient

Today, Phnom Penh Noodle House is a Seattle institution of 30 years, and one that has survived more than its fair share of challenges. It has reopened — in a limited capacity, due to the COVID-19 pandemic — after a nearly two-year hiatus, on South Jackson Street.

But the story really starts with a noodle cart.

Phnom Penh Noodle House traces its origin back three generations, to an early 1940s mobile food operation on the streets of Battambang, Cambodia.

Cheng Ung was 14 years old in 1937 when he fled China to avoid conscription in the army amid the Sino-Japanese War. He settled in Cambodia, where he first worked as a farm laborer. After a few years, he started his noodle cart business, which he eventually ran with his wife, Meng Tan. That two-person operation gradually grew into a full-scale restaurant with lines that stretched out the door for noodle soup, congee, and desserts.

Their son, Sam Ung, grew up mesmerized by the cooks in his parents’ restaurant in Battambang, watching in awe as they kept food moving from wok to plate. He worked his way up, starting with chopping vegetables and meat at age 14. He was a salaried employee by 15, and backup for the lead cook at 16.

Sam likely saw his future in that restaurant. Perhaps he would raise his own children in the kitchen, where they’d learn the business from the ground up, just as he had. But the trajectory of his life changed completely in 1975 — much like his father’s had before him.

A civil war in Cambodia brought the rise of the violent Khmer Rouge regime, which exacted widespread imprisonment, torture, and genocide. Over its four-year rule in the ’70s, the Khmer Rouge was responsible for one of the 20th century’s worst mass killings.

By 1980, Sam and his then-wife Kim — who was pregnant with their first daughter, Dawn — made their way from a refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border to settle in Seattle. With few resources, Sam scratched out a living with two jobs, at Ivar’s Acres of Clams and the Rainier Club.

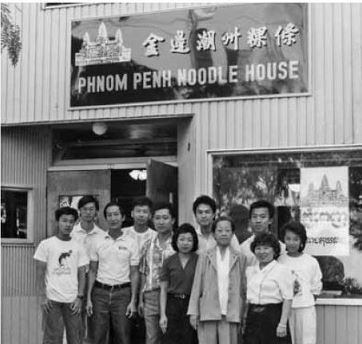

When a small restaurant space became available, Sam opened the first iteration of Phnom Penh Noodle House in 1987, in the Chinatown-International District. He continued cooking at the Rainier Club to keep the family and the fledgling business, afloat.

“They immigrated as refugees, and they had nothing with them and were learning a new culture and language and were trying to acclimate,” Sam’s daughter Diane Le says.

“When they opened the restaurant, they had no understanding of how businesses here are run. And Dad did it. He wore every single hat and just made it happen.”

Back then, the restaurant had 30 to 40 seats and seven items on the menu. A decade in, the roof of the building collapsed under heavy snow, and Phnom Penh Noodle House relocated to a much larger space with room for 120 diners on South King Street. The menu grew alongside a robust catering business.

Sam and Kim eventually had three daughters, Dawn, Diane, and Darlene, who all grew up in their parents’ restaurant. Diane, now the restaurant’s unofficial spokesperson, remembers taking the bus down Jackson Street after she finished classes at Garfield High School. She and her sisters would do their homework, then fill in as servers and have dinner. “We grew up on noodles,” Diane says.

The girls saw Phnom Penh Noodle House grow into a community staple. “People who finished kung fu class upstairs, they’d congregate afterwards in the restaurant,” Diane says. “The various Cambodian associations would have meetings there.”

he restaurant hosted birthdays, graduation parties, and first dates that became wedding anniversary celebrations. Phnom Penh was a second home for multiple generations of patrons. Sam became a respected community member, not just for his food but for his charity work, volunteering and donating food through the Asian Counseling and Referral Service.

And though Sam always told his daughters they were free to pursue other careers — and to a large extent, early on in adulthood, they did — the restaurant called them back. When Sam retired in 2013 as owner and head chef, Dawn and Darlene took over the day-to-day operations, with occasional help from Diane. Darlene’s husband, Peng Liu, became chef.

Dawn, Darlene, and Peng kept the restaurant firing on all burners for five years. But everything changed on September 26, 2017, when Dawn’s son, Devin Cropp, then a high school senior, was hit by a car while walking home from an ultimate frisbee game. The collision caused extensive injuries that required multiple major surgeries — the kind of accident that changes an entire family’s trajectory forever.

There were many challenges that came from running a large, busy restaurant and a flourishing catering business, and the ownership team had already been considering downsizing when the accident happened.

Dawn stepped away from the restaurant to concentrate on caring for Devin, who spent more than a year in hospital. Medical expenses piled up, and even once he was released, Devin needed around-the-clock care.

The sisters decided to shut down Phnom Penh after service on May 28, 2018. Distraught customers poured into the restaurant to buy a meal and express their sympathies. The outpouring showed up everywhere — in comments on the restaurant’s Facebook page and on news stories about the closure.

When a family friend launched a GoFundMe campaign to help with Devin’s mounting medical expenses — including a $14,000 wheelchair lift on a new van — fans of the restaurant were among the contributors.

“Your restaurant was a big part of my childhood that carried into adulthood. Thank you sharing your restaurant with me, my friends and family. It’s my turn to give back and say thank you to you and your family,” wrote donor Tran Dao. To date, the fundraiser, which is still active, has raised more than $91,000 toward a $150,000 goal.

“People came out of nowhere, helping in any way they could, even if it was just a couple hundred dollars. Every little bit really does count,” Diane says. The possibility of reopening was always in the back of their minds. “We had something really special, and that’s just something you don’t want to lose.”

Gradually, the sisters started getting serious about reopening. With Seattle rents at a premium, they scouted locations in Renton and Kent. Then, a former customer told them about a new building in the International District she was brokering. The developer was offering tenant improvement funds that would ease some of the financial burden of opening a new restaurant.

Once again, the community rallied around them, and the list of people who pitched in — from donations through an Indiegogo campaign to space for pop-ups and pro bono legal assistance — was long. It seemed each complex layer involved in building out the new restaurant found support. “It takes an entire village to make this happen,” Diane says.

More help came in the form of a $140,000 grant from the city of Seattle’s Office of Economic Development, and assistance from the Seattle Chinatown International District Preservation and Development Authority. Although the family once again found themselves starting over, this time they wouldn’t be starting from zero.

As Devin’s situation stabilized, Dawn redirected some energy back toward the restaurant. But Devin, who suffered a traumatic brain injury, will likely need significant care for the rest of his life. On the consciousness scale, Diane says, “We would be ranked at a 9, because we’re conscious, fully aware, we can comprehend and we have cognitive awareness. Whereas Devin is like a 1.5. He’s got movement and sometimes maybe eye contact but he’s still nonverbal, and maybe not fully conscious of where he is or who we are.”

The restaurant was originally set to reopen fully in March, but the chaos of the pandemic and the economic shutdown extinguished those plans. It was just one more challenge facing a family that seems to have resiliency written into its DNA.

Sticking to the original plan, Phnom Penh began serving takeout again in April and then offering some indoor dining under Washington State’s phased “Safe Start” reopening plan, when Seattle got the green light to allow seating at 50 percent capacity.

Newly reborn, Phnom Penh Noodle House sports a redesigned logo and a slick space that’s more modern and representative of the generation currently at the helm. The menu is pared down, but fan favorites, including the honey-black pepper chicken wings, prawn and fish cake noodle soup, mee katang (wide rice noodles in gravy), and beef lok lac (wok-tossed marinated steak cubes), are still there.

It’s a welcome development for scores of diners who consider this restaurant more than just a place to get a good bowl of soup — it’s the return of an essential gathering place, an indispensable thread in a vibrant community web.

But even if you just come for the food, Sam Ung doesn’t think you’ll leave disappointed.

“I traveled around Cambodia trying noodles. I haven’t found any that has beaten mine yet, from the fancy restaurants to the street vendors. I’ve tried them all,” Sam says. “I still think, ‘Mine are better. Mine are better.’”